On the morning of Monday, August 13, 2012, Scott Stevens loaded a brown hunting bag into his Jeep Grand Cherokee, then went to the master bedroom, where he hugged Stacy, his wife of 23 years. “I love you,” he told her.

Stacy thought that her husband was off to a job interview followed by an appointment with his therapist. Instead, he drove the 22 miles from their home in Steubenville, Ohio, to the Mountaineer Casino, just outside New Cumberland, West Virginia. He used the casino ATM to check his bank-account balance: $13,400. He walked across the casino floor to his favorite slot machine in the high-limit area: Triple Stars, a three-reel game that cost $10 a spin. Maybe this time it would pay out enough to save him.

It didn’t. He spent the next four hours burning through $13,000 from the account, plugging any winnings back into the machine, until he had only $4,000 left. Around noon, he gave up.

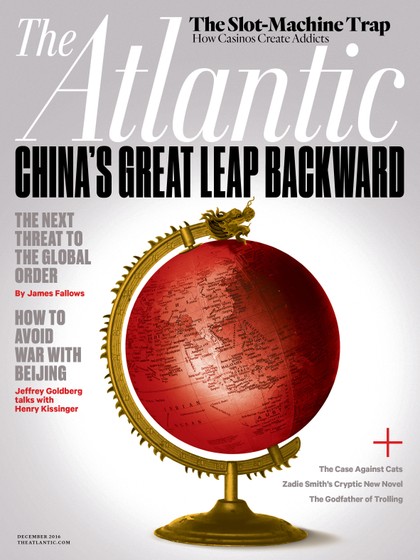

FROM OUR DECEMBER 2016 ISSUE Subscribe to The Atlantic and support 160 years of independent journalism

Subscribe to The Atlantic and support 160 years of independent journalism

SubscribeStevens, 52, left the casino and wrote a five-page letter to Stacy. A former chief operating officer at Louis Berkman Investment, he gave her careful financial instructions that would enable her to avoid responsibility for his losses and keep her credit intact: She was to deposit the enclosed check for $4,000; move her funds into a new checking account; decline to pay the money he owed the Bellagio casino in Las Vegas; disregard his credit-card debt (it was in his name alone); file her tax returns; and sign up for Social Security survivor benefits. He asked that she have him cremated.

He wrote that he was “crying like a baby” as he thought about how much he loved her and their three daughters. “Our family only has a chance if I’m not around to bring us down any further,” he wrote. “I’m so sorry that I’m putting you through this.”

He placed the letter and the check in an envelope, drove to the Steubenville post office, and mailed it. Then he headed to the Jefferson Kiwanis Youth Soccer Club. He had raised funds for these green fields, tended them with his lawn mower, and watched his daughters play on them.

Stevens parked his Jeep in the gravel lot and called Ricky Gurbst, a Cleveland attorney whose firm, Squire Patton Boggs, represented Berkman, where Stevens had worked for 14 years—until six and a half months earlier, when the firm discovered that he had been stealing company funds to feed his gambling habit and fired him.

Stevens had a request: “Please ask the company to continue to pay my daughters’ college tuition.” He had received notification that the tuition benefit the company had provided would be discontinued for the fall semester. Failing his daughters had been the final blow.

Gurbst said he would pass along the request.

Then Stevens told Gurbst that he was going to kill himself.

“What? Wait.”

“That’s what I’m going to do,” Stevens said, and promptly hung up.

He next called J. Timothy Bender, a Cleveland tax attorney who had been advising him on the IRS’s investigation into his embezzlement. Up until that point, he had put on a brave face for Bender, saying he would accept responsibility and serve his time. Now he told Bender what he was about to do. Alarmed, Bender tried to talk him out of it. “Look, this is hard enough,” Stevens said. “I’m going to do it.” Click.

At 4:01 p.m., Stevens texted Stacy. “I love you.” He then texted the same message to each of his three daughters in succession.

He took off his glasses, his glucose monitor, and his insulin pump—Stevens was a diabetic—and tucked them neatly into his blue thermal lunch bag with the sandwich and apple he hadn’t touched.

He unpacked his Browning semiautomatic 12-gauge shotgun, loaded it, and sat on one of the railroad ties that rimmed the parking lot.

Then he dialed 911 and told the dispatcher his plan.

Scott stevens hadn’t always been a gambler. A native of Rochester, New York, he earned a master’s degree in business and finance at the University of Rochester and built a successful career. He won the trust of the steel magnate Louis Berkman and worked his way up to the position of COO in Berkman’s company. He was meticulous about finances, both professionally and personally. When he first met Stacy, in 1988, he insisted that she pay off her credit-card debt immediately. “Your credit is all you have,” he told her.

They married the following year, had three daughters, and settled into a comfortable life in Steubenville thanks to his position with Berkman’s company: a six-figure salary, three cars, two country-club memberships, vacations to Mexico. Stevens doted on his girls and threw himself into causes that benefited them. In addition to the soccer fields, he raised money to renovate the middle school, to build a new science lab, and to support the French Club’s trip to France. He spent time on weekends painting the high-school cafeteria and stripping the hallway floors.

Stevens got his first taste of casino gambling while attending a 2006 trade show in Las Vegas. On a subsequent trip, he hit a jackpot on a slot machine and was hooked.

Scott and Stacy soon began making several trips a year to Vegas. She liked shopping, sitting by the pool, even occasionally playing the slots with her husband. They brought the kids in the summer and made a family vacation of it by visiting the Grand Canyon, the Hoover Dam, and Disneyland. Back home, Stevens became a regular at the Mountaineer Casino. Over the next six years, his gambling hobby became an addiction. Though he won occasional jackpots, some of them six figures, he lost far more—as much as $4.8 million in a single year.

Did Scott Stevens die because he was unable to rein in his own addictive need to gamble? Or was he the victim of a system carefully calibrated to prey on his weakness?Stevens methodically concealed his addiction from his wife. He handled all the couple’s finances. He kept separate bank accounts. He used his work address for his gambling correspondence: W-2Gs (the IRS form used to report gambling winnings), wire transfers, casino mailings. Even his best friend and brother-in-law, Carl Nelson, who occasionally gambled alongside Stevens, had no inkling of his problem. “I was shocked when I found out afterwards,” he says. “There was a whole Scott I didn’t know.”

When Stevens ran out of money at the casino, he would leave, write a company check on one of the Berkman accounts for which he had check-cashing privileges, and return to the casino with more cash. He sometimes did this three or four times in a single day. His colleagues did not question his absences from the office, because his job involved overseeing various companies in different locations. By the time the firm detected irregularities and he admitted the extent of his embezzlement, Stevens—the likable, responsible, trustworthy company man—had stolen nearly $4 million.

Stacy had no idea. In Vegas, Stevens had always kept plans to join her and the girls for lunch. At home, he was always on time for dinner. Saturday mornings, when he told her he was headed into the office, she didn’t question him—she knew he had a lot of responsibilities. So she was stunned when he called her with bad news on January 30, 2012. She was on the stairs with a load of laundry when the phone rang.

“Stace, I have something to tell you.”

She heard the burden in his voice. “Who died?”

“It’s something I have to tell you on the phone, because I can’t look in your eyes.”

He paused. She waited.

“I might be coming home without a job today. I’ve taken some money.”

“For what?”

“That doesn’t matter.”

“How much? Ten thousand dollars?”

“No.”

“More? One hundred thousand?”

“Stace, it’s enough.”

Stevens never did come clean with her about how much he had stolen or about how often he had been gambling. Even after he was fired, Stevens kept gambling as often as five or six times a week. He gambled on his wedding anniversary and on his daughters’ birthdays. Stacy noticed that he was irritable more frequently than usual and that he sometimes snapped at the girls, but she figured that it was the fallout of his unemployment. When he headed to the casino, he told her he was going to see his therapist, that he was networking, that he had other appointments. When money appeared from his occasional wins, he claimed that he had been doing some online trading. While they lived off $50,000 that Stacy had in a separate savings account, he drained their 401(k) of $150,000, emptied $50,000 out of his wife’s and daughters’ ETrade accounts, maxed out his credit card, and lost all of a $110,000 personal loan he’d taken out from PNC Bank.

Stacy did not truly understand the extent of her husband’s addiction until the afternoon three police officers showed up at her front door with the news of his death.

Afterward, Stacy studied gambling addiction and the ways slot machines entice customers to part with their money. In 2014, she filed a lawsuit against both Mountaineer Casino and International Game Technology, the manufacturer of the slot machines her husband played. At issue was the fundamental question of who killed Scott Stevens. Did he die because he was unable to rein in his own addictive need to gamble? Or was he the victim—as the suit alleged—of a system carefully calibrated to prey upon his weakness, one that robbed him of his money, his hope, and ultimately his life?

Less than 40 years ago, casino gambling was illegal everywhere in the United States outside of Nevada and Atlantic City, New Jersey. But since Congress passed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act in 1988, tribal and commercial casinos have rapidly proliferated across the country, with some 1,000 now operating in 40 states. Casino patrons bet more than $37 billion annually—more than Americans spend to attend sporting events ($17.8 billion), go to the movies ($10.7 billion), and buy music ($6.8 billion) combined.

The preferred mode of gambling these days is electronic gaming machines, of which there are now almost 1 million nationwide, offering variations on slots and video poker. Their prevalence has accelerated addiction and reaped huge profits for casino operators. A significant portion of casino revenue now comes from a small percentage of customers, most of them likely addicts, playing machines that are designed explicitly to lull them into a trancelike state that the industry refers to as “continuous gaming productivity.” (In a 2010 report, the American Gaming Association, an industry trade group, claimed that “the prevalence of pathological gambling … is no higher today than it was in 1976, when Nevada was the only state with legal slot machines. And, despite the popularity of slot machines and the decades of innovation surrounding them, when adjusted for inflation, there has not been a significant increase in the amount spent by customers on slot-machine gambling during an average casino visit.”)

“The manufacturers know these machines are addictive and do their best to make them addictive so they can make more money,” says Terry Noffsinger, the lead attorney on the Stevens suit. “This isn’t negligence. It’s intentional.”

Noffsinger, 72, has been here before. A soft-spoken personal-injury attorney based in Indiana, he has filed two previous lawsuits against casinos. In 2001, he sued Aztar Indiana Gaming, of Evansville, on behalf of David Williams, then 51 years old, who had been an auditor for the State of Indiana. Williams began gambling after he received a $20 voucher in the mail from Casino Aztar. He developed a gambling addiction that cost him everything, which in his case amounted to about $175,000. Noffsinger alleged that Aztar had violated the 1970 Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act by engaging in a “pattern of racketeering activity”—using the mail to defraud Williams with continued enticements to return to the casino. But the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana granted summary judgment in favor of Aztar, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit instructed the district court to dismiss the case, declaring, “Even if the statements in these communications could be considered ‘false’ or ‘misrepresentations,’ it is clear that they are nothing more than sales puffery on which no person of ordinary prudence and comprehension would rely.”

Four years later, Noffsinger filed a suit on behalf of Jenny Kephart, then 52 years old, against Caesars Riverboat Casino, in Elizabeth, Indiana, alleging that the casino, aware that Kephart was a pathological gambler, knowingly enticed her into gambling in order to profit from her addiction. Kephart had filed for bankruptcy after going broke gambling in Iowa, and moved to Tennessee. But after she inherited close to $1 million, Caesars began inviting her to the Indiana riverboat casino, where she gambled away that inheritance and more. When the casino sued her for damages on the money she owed, Kephart countersued. She denied the basis of the Caesars suit on numerous grounds, including that by giving her “excessive amounts of alcohol … and then claiming that it was injured by her actions or inactions,” Caesars waived any claim it might have had for damages under Indiana law. Although Kephart ultimately lost her countersuit, the case went all the way to the Indiana Supreme Court, which ruled in 2010 that the trial court had been mistaken in denying Caesars’s motion to dismiss her counterclaim. “The existence of the voluntary exclusion program,” the judge wrote, referring to the option Indiana offers people to ban themselves from casinos in the state, “suggests the legislature intended pathological gamblers to take personal responsibility to prevent and protect themselves against compulsive gambling.” (Caesars did not respond to repeated requests for comment.)

Noffsinger had been planning to retire before he received Stacy Stevens’s phone call. But after hearing the details of Scott Stevens’s situation—which had far more serious consequences than his previous two cases—he eventually changed his mind. Unlike in his earlier gambling cases, however, he decided to include a products-liability claim in this one, essentially arguing that slot machines are knowingly designed to deceive players so that when they are used as intended, they cause harm.

In focusing on the question of product liability, Noffsinger was borrowing from the rule book of early antitobacco litigation strategy, which, over the course of several decades and countless lawsuits, ultimately succeeded in getting courts to hold the industry liable for the damage it wrought on public health. Noffsinger’s hope was to do the same with the gambling industry. When Noffsinger filed the Stevens lawsuit, John W. Kindt, a professor of business and legal policy at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, described it as a potential “blockbuster case.”

Even by the estimates of the National Center for Responsible Gaming, which was founded by industry members, 1.1 to 1.6 percent of the adult population in the United States—approximately 3 million to 4 million Americans—has a gambling disorder. That is more than the number of women living in the U.S. with a history of breast cancer. The center estimates that another 2 to 3 percent of adults, or an additional 5 million to 8 million Americans, meets some of the American Psychiatric Association’s criteria for addiction but have not yet progressed to the pathological, or disordered, stage. Others outside the industry estimate the number of gambling addicts in the country to be higher.

Such addicts simply cannot stop themselves, regardless of the consequences. “When you’re dealing with an addict active in their addiction, they’ve lost all judgment,” says Valerie Lorenz, the author of Compulsive Gambling: What’s It All About? “They can’t control their behavior.”

Gambling is a drug-free addiction. Yet despite the fact that there is no external chemical at work on the brain, the neurological and physiological reactions to the stimulus are similar to those of drug or alcohol addicts. Some gambling addicts report that they experience a high resembling that produced by a powerful drug. Like drug addicts, they develop a tolerance, and when they cannot gamble, they show signs of withdrawal such as panic attacks, anxiety, insomnia, headaches, and heart palpitations.

Unfortunately, some percentage of people develop harmful addiction when they are too involved in online gaming. Therefore, it has to be properly handled. You should be able to control how much money you can spend on casino games https://richprize.com/games/egt. When you cannot stop playing, it is the first sign that something went wrong here. Be careful when playing for real money.